From the Origins

OR THE PORT OF HERCULES' SON

«…because being (…) set against some rugged cliffs by the sea, which the common people call Leixoens; as much as the enraged storms may display on them with their capped swelling and horrendous deliquescences, never has there been a shipwreck in them, but rather a safe haven for every vessel, which purposely sets its course to this marvelous anchorage, to save itself from complete ruin, which would otherwise be inevitable destruction and notorious peril, thus achieving calmness in the most furious storm.»

António Cerqueira Pinto, História da Prodigiosa Image..., 1737

It was God or Nature's will that at the mouth of the river Leça, halfway along the coast, a cluster of rocks rose from the Atlantic waters, which men named "Leixões." There were the "Espinheiro," the "Alagadiça," the large and small "Leixão," just as there were large and small rocks of "Lada." But there were also the "Tringalé," the "Galinheiro," the "Cavalo de Leixão," the "Quilha," the "Baixa do Moço," the "Fuzilhão," the "Baixo do Leixão Velho," and many others...

Whether divine design or simply capricious granite outcrops, classified by geologists as medium-grained or gneissic, the Leixões formed a semicircle in the sea, creating a natural harbor.

On a coast often ravaged by storms and fogs, dangerous due to the presence of abundant treacherous rocks visible only at low tide, which greatly contributed to the somber and ominous title of "Black Coast" given to this region for centuries, the refuge naturally formed by the Leixões could not escape the attention and shrewdness of men. And indeed, since the remotest antiquity, it is human intervention, more than natural or divine, that would shape the history of Leixões. Even if, for this purpose, mortals have often faced the adversities imposed by nature, and many times have overcome what seemed to be divine opposition or, who knows, the will of the Devil.

The Leça river itself contributed to and reinforced the appeal of the shelter. Flowing gently in this final stage of its journey, the river emptied into an inviting estuary, navigable upstream for a considerable distance. Such potential was already exploited in the 1st millennium B.C. when, very close to its mouth, on a rise of the left bank now called Monte Castêlo, an important Iron Age settlement emerged: the Castro de Guifões, inhabited by Bracari Galicians. At the base of the hill, near the river, undoubtedly, a port structure developed, albeit rudimentary. Archaeological findings attest to the arrival - by sea - of products from distant lands..

Colonized by the Romans from the 1st century B.C., the Castro de Guifões now belongs, and integrates with remarkable success, into the vast economic and commercial space that is the Roman Empire. Safeguarded by the Leixões and led to the elevation where this settlement was located through the Leça River, the ships of the time brought here agricultural produce from the south of the Peninsula, fish preserves from the Sado estuary, ceramics, and other expressions of the material culture from Italy, southern France, North Africa, the eastern Mediterranean... In this way, the mouth of the Leça river became, two thousand years ago, an important port and commercial interface for the region, especially for the other settlements that were located in the basin of this river or in its vicinity. And, since then, throughout History, the mouth of the Leça and its maritime-fluvial port never ceased to possess such importance. Sometimes on a reduced regional scale, often influencing vast areas.

Meanwhile, Roman domination also resulted in a more dispersed settlement and contributed to a greater approximation of populations to the maritime coastline and riverbanks. In this context, still during the first centuries of our Era, the occupation of the space now coincident with the city of Matosinhos-Leça began. And if for this latter parish, located on the right bank of the mouth of the Leça River, archaeology has recently revealed evidence of such remote occupation, for the case of Matosinhos, on the left bank, it is the very origin of the toponym that, according to some researchers, is decisively associated with the Roman era and the origin of the port. It is worth taking a moment to consider this hypothesis, which curiously will once again lead the reader to encounter a relationship that men wanted to establish between Leixões and the divine, in this case based on Roman mythology.

In the oldest documents in which the name Matosinhos appears, dated from the 10th century and written in Latin, it is designated as Matesinus, a toponym that, by itself, is difficult to explain or understand.

However, by subdividing the word, interesting explanatory clues about the origin of the toponym emerge. In fact, "sinus" meant in Latin, and particularly for the Romans, a cut in the coastline, concave on the coast... a natural harbor. That is, something that, as we have already analyzed, perfectly adapted to the geo-topographical reality that the Romans found here, due to the existence of the Leixões. Moreover, the vast Roman world is full of toponyms that have the mentioned designation "sinus" in their origin or as a component. Another illustrative example, in Portugal, is that of Sines.

Having explained the origin of half of the word, it remains to understand the meaning of "Mate." Since the Romans had the habit of naming the main cities, ports, and other places of geo-strategic interest they founded or conquered with the names of deities, emperors, heroes, or figures drawn from mythology, it is in this field that some scholars have found a possible and, at the very least, curious explanation (1). The fact is that there is a mythological character, a son of Hercules, whose designation – Amato – could easily be at the origin of the current toponym. Matosinhos would thus result, as we know, from Matesinus, and this, in turn, could derive from Amato sinus: the harbor of refuge of the son of Hercules.

A natural sheltered harbor that, in fact, saved thousands of lives of sailors, seafarers, passengers, and fishermen for many centuries. Because, as Marino Franzini wrote in 1812,

"perhaps this is the only point on this coast that offers any shelter to boats assailed by the crossing; and, in any case, it is the only stop where crews can have hope of salvation when running aground is inevitable. The boats of pilots and fishermen can almost always set out to sea from this point, when it is impracticable due to the surf at any other point along the coast."

However, Leixões' natural harbor will be transformed, at the end of the 19th century, into a gigantic artificial port structure. In one of the most dynamic places where Europe meets and embraces the Atlantic. However, that is another story. One that we will try to narrate next, necessarily in an abbreviated form.

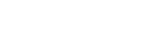

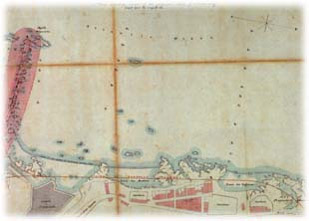

"(…) Map is a demonstration of the Coastline from the Town of Matosinhos to the Mouth of the City of Portoo (…)"

By José Gomes da Cruz, Pilot of Warships. 1775

Copy from 1906. APDL Archive..

From the Origins

Or the evidence of the usefulness of an artificial port at Leixões.

"In a distance of a quarter of a league to the sea, in a straight line from the mouth of the river, a large and flat area of rock is uncovered, (...) engineers say that it is possible to build a causeway to walk dry to said large cliff called Leyxoens and build a good fortress for the defense of an excellent anchorage of a large number of ships, very useful for all time, much more so for when they cannot enter the port bar, due to its continuous dangers."

Pde. Luís Cardoso, Parochial Memoirs, 1758

The natural conditions were therefore gathered so that at the mouth of the river Leça, and taking advantage of the shelter formed by the Leixões, an artificial port could be built. The will of the people is also evident from very early on. But it's not enough...

Building "a causeway to walk dry" from the beach to the Leixões, thus defining a safe artificial harbor for a "large number of ships," is a project of great utility dreamed of - prematurely, some would say - since at least the sixteenth century. But what for many is almost crystal clear evidence, for others is totally and radically ignored. This blindness will be found among the powerful and those who, after all, paradoxically would profit most from the construction of such an enterprise: the merchant bourgeoisie, and later industrial, of the city of Porto.

Although requests and projects to transform the natural harbor into a port structure began to become systematic from the reign of King João V, we already find some references before, such as a study authored by Simão de Ruão, dated 1567. But it is indeed from the second half of the eighteenth century that the plans multiply. Such as those of Salazar in 1779, Oudinot in 1789, Gomes de Carvalho in 1816, Alves de Sousa in 1840, or Damásio in 1844.

However, it was no longer just the evidence of possibility and usefulness that motivated these studies. The Leixões themselves were no longer the sole stimulus for such ideas. Another factor, located five kilometers further south, was gaining more and more weight: the possibility of being an alternative, a shelter, for ships, increasingly numerous, that at certain times of the year "cannot enter the port bar, due to its continuous dangers."

Special mention deserves the "Map (...) demonstration of the Coast of the Sea from the Villa of Matozinhos, to the Bar of the City of Porto" by Jozé Gomes da Cruz, Pilot of Warships, dated 1775, which defended the following project:

« (…) in front of the said village (Matosinhos) is represented the great stone of Leixões, which can serve as a seat for a castle, under the shade of which the ships that cannot enter the Bar of the said City of Porto can take shelter, it can also be filled from the North with old ships loaded with stone, a space that exists between the said stone and others that remain to the North (…) from this work will result in times of War avoiding that the Ships go to Galicia and there remain prisoners, or get lost going run with a storm (…) the ships will thus be sheltered from the South, West, Northwest, and North winds, and the other winds will not be able to cause much damage to them (…) ».

Indeed, the mouth of the Douro River has always been a particularly painful obstacle for the boats that, penetrating through its bar, sought to reach, upstream, the various docks of the port of Douro, the most important of which were located on the right bank, next to the riverside and historic areas of the city of Porto, such as the Ribeira, Bicalho, Ouro, Cantareira docks...

A dangerous entrance, full of numerous and unexpected rocks, some emerging, others hidden, caused repeated and tragic shipwrecks. A simple analysis of the "Geographical Map of the Bar of Porto" included in the work Topographical and Historical Description of the city of Porto, authored by Agostinho Rebello da Costa, dated 1789, is quite elucidative in this regard. On the other hand, the fact that the Douro is a river of great and cyclical floods, which prevented its navigability for long periods, associated with the circumstance that, in contrast, the bar was often quite silted up in the remaining seasons, contributed to making the Douro effectively a port of great dangers and difficulties for maritime traffic. Even greater as there was also a progressive increase in the draft of the ships. From this unbearable situation, particularly for commercial navigation, John Rennie's report, dated June 14, 1855, echoes eloquently

« ohe existing dangers and the loss of lives that had occurred, as well as the losses suffered by commerce due to the difficulty in entering the bar, which in winter and early spring was sometimes closed for weeks and months on end, with cases of a ship making a round trip to Brazil, while another waited outside the bar for an opportunity to enter the port. In the summer itself, the sea sometimes prevented communication between ships and the interior of the port » (3).

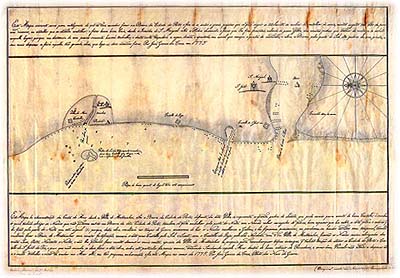

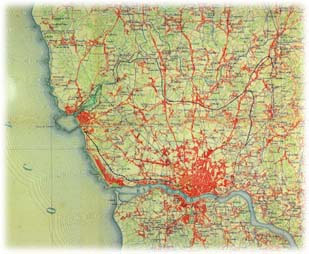

"Geographical Map of the Bar of the City of Porto," in Agostinho Rebello da Costa,

Topographical and Historical Description of the city of Porto, 1789.

Archive of the APDL.

Would the natural conditions, divine designs, and human will finally be gathered to advance with the construction of an artificial port supported by the Leixões? Everything would lead one to believe so. But it wasn't that easy. The devil or – if you prefer a more historiographical interpretation – the socio-economic context of the time, still posed many obstacles throughout the second half of the 19th century.

It wasn't easy, particularly for the bourgeois of Porto, to give up the Douro port. For centuries, the city had developed its commercial activity in a particularly privileged, almost conspiratorial, manner with the river. The city had even grown in intimate relation to this watercourse. In its riverside areas, we find the main economic-commercial structures of the city. And this holds true for the entire nineteenth century. The stock exchange, the customs, the English factory, the headquarters and warehouses of the main commercial companies of the town... And, in the second half of the 19th century, in clear articulation with the riverfront quays, it is also the industrial settlement that will once again shape and tighten the city's connection with its river.

In this context, could the bourgeois of Porto of that time accept, in a peaceful manner, the transfer of their commercial and port world from the Douro to Leixões? The answer was a resounding no. A no materialized in total deafness and blindness towards proposals that pointed to Leixões as a safe alternative to the Douro. A no that, beyond the reasons founded on the historical and emotional ties that this community had with the river, took into account much more immediacy, and very little future perspective. Because, as one can easily understand, for the commercial and industrial bourgeoisie of the city, it was not at all appealing, from an economic point of view and in the short term perspective, to have to dismantle, transfer, or adapt their warehouses, factories, and other riverside structures. Even though they intuited that in the medium/long term, the option for Leixões would surely be more profitable.

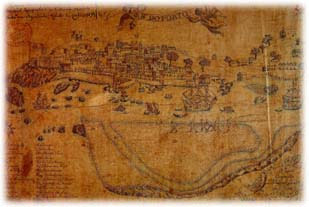

"View of the banks of the Douro River ascending towards the City of Porto."

Date unknown (1st half of the 19th century).

Archive of the APDL.

And, subscribing to the opinion of the economic power (or, at least, of important and influential commercial sectors of Porto), the political power will also ignore the enlightened spirits who saw the solution in the construction of an alternative port at the mouth of the Leça River.

And so, the stubbornness of men prevailed more than would be understandable. To prevent constant shipwrecks and lengthy waits to cross the bar, measures were taken that, although desperate and simultaneously imbued with the purest hope of resolving the problem of safe navigation of the old commercial port of the Douro, never amounted to more than palliatives. However, some interventions at the mouth that have survived to this day were highlighted. Such as the downstream dike of Cantareira, including the "Half Orange," according to Engineer Oudinout's second project, built between 1792 and 1805, and another 600-meter dike at the northern end of Cabedelo, now designated as the Luiz Gomes de Carvalho pier, a personality who directed its construction between 1820 and 1825.

But there were many works and projects since the late 18th century. In 1790, at the initiative of the Royal Companhia Velha, the construction of the marginal road connecting Porto to Foz-do-Douro was started near Arrábida, which in the following years allowed for the appearance and connection by land of new and better docks, such as Arrábida, Cantareira, Monchique, Massarelos, and even Ribeira.

But it wasn't the new docks, and better accessibility to them by land, that would solve the navigation problem. The dangers of the Douro bar remained and accidents continued to occur. And it is following a tragic shipwreck, on March 29, 1852, with the steamship "Porto," thrown by the rough sea onto the rocks of Forcada, in front of the Castle of São João da Foz, in which 66 people died, that the authorities finally engage in the search for a solution. A search that, from the outset, continues to focus on the Douro River. However, gradually, Leixões was emerging and asserting itself as the obvious answer...

PPlan of the Improvements of the Commercial Port of Douro - Right Bank from Luiz 1st Bridge to Massarelos. 1887.

1890 Copy. APDL Archive

A few days after the shipwreck of the "Porto," the Government appoints a commission, headed by Engineer Belchior Garcez, to propose whatever was deemed necessary to increase the safety of the Douro. It was just the beginning. Many other projects, studies of currents, evaluations of floods, proposals, and actual destruction of rocks and breaking of rocks, construction of new docks, jetties, and embankments, followed in the subsequent decades, under the responsibility of many other commissions or engineers, many of them foreigners, especially hired for this purpose. The list would be immense, and the reader's patience would be exhausted. Nevertheless, let us stubbornly recall some:

1854 - French engineer Gayffier proposes a dock from Passeio Alegre to the rocks of Felgueiras;

1854 - London engineer William Jates Freebody is hired to examine the Douro bar and prepare a report with solutions;

1855 - another Englishman, hydraulic engineer Sir John Rennie, presents a report advocating the destruction of a series of rocks;

1858 - English engineer Knox presents a project that foresaw the filling of the river mouth, opening a canal with a lock at Cabedelo that would lead to a sheltered harbor built in the sea and formed by maritime jetties;

1859 - projects by engineer Joaquim Nunes de Aguiar and Public Works inspector José Carlos Chelmiki;

1859 to 1862 - detailed hydrographic studies led by engineer Caetano Maria Batalha, who also concludes the need for the destruction of numerous rocks, many of which should reach depths of up to six meters;

1863 - French engineer H. Luzeu advocates changing the orientation of the Douro entrance, suggesting the construction of two curvilinear jetties from Cabedelo and S. João da Foz, effectively changing the course of the Douro waters at its contact with the sea. Another project, like so many others, that remained on paper. The same would happen with those of Léo de La Peyrouse and Robert Messer, both from 1865.

However, conclusive were the studies directed by engineer Afonso Joaquim Nogueira Soares from 1869 to 1871. His proposals, approved by the Government in 1873, although with successive modifications and improvements, were effectively implemented in works he directed until 1892. It is from this period, among others, the construction of the northern jetty of Foz do Douro, the embankment of Praia das Argolas, the filling of Passeio Alegre, the slipway of Cantareira, the jetty of Carreiros, the jetty of Felgueiras or Farolim…

But, by this time, the reader may be tired of dates, names, and projects. And the question, we guess, is in their mind: Yes... but Leixões?

In this large set of studies and projects, from an early stage, Leixões and the mouth of the Leça River appear as the ideal alternative to the old commercial port of Douro. Some of the most eminent foreign engineers, to whom the government had requested opinions, have no doubt about it. Although the author of the aforementioned project, the construction of two jetties at the mouth of the Douro to allow a change in the direction of the river's waters at its mouth, the Frenchman Luzeu clearly advocates the alternative of building a new port. Those who not only advocated such a possibility but also advanced with projects were also the aforementioned Englishmen Freebody and Rennie, both in 1855.

Thus, despite being successively postponed and the interests at stake against its effective materialization, the idea of a port at Leixões was gaining ground and supporters. Even more so when, ten years later, dated March 17, 1865, a new project, authored by engineer Manuel Afonso Espregueira, which foresaw the construction of two jetties rooted in the beach, managed to gather the necessary consensus to obtain, three years later, the favorable opinion of the Public Works Council.

But it would still be necessary to wait a few more years. Time for English engineer James Abernethy to produce two plans and for two characters to appear on the scene who, technically, would definitively produce the project for the Port of Leixões: the Englishman Sir John Coode and the already known Afonso Joaquim Nogueira Soares - the engineer who had been directing the works at the mouth of the Douro. It is indeed based on the projects presented in 1878 by Nogueira Soares and in 1881 by Coode that, in 1883, the Minister of Public Works, Hintze Ribeiro, presents to the Chamber of Deputies a Bill authorizing the Government to award the construction of the artificial sheltered port of Leixões. And, considering some modifications necessary, engineer Nogueira Soares is responsible for the elaboration of the definitive project, which he completed on August 24, 1883. It is fair to mention the name of Adolpho Loureiro, who during this period was part of a series of commissions that accompanied the final project development.

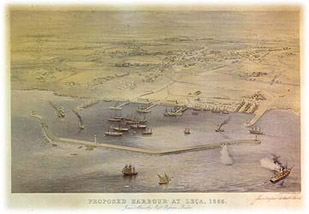

Proposed Harbour at Leça, 1865

(James Abernethy's Proposal for a port at the mouth of Leça)

APDL Archive

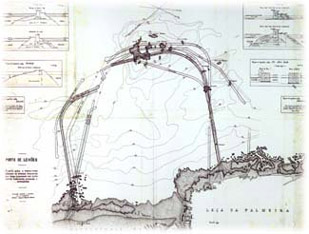

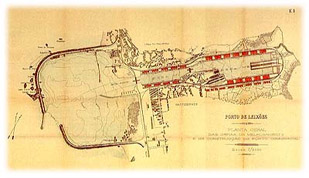

Port of Leixões. General Plan and Typo-profiles according to the various projects elaborated by different national and foreign Engineers.

Scale 1/2,500 (original).

Date unknown. APDL Archive

And so, after many decades of waiting (centuries for the most visionary), in that same year of 1883, an international tender was opened for the definitive construction of the Port of Leixões. The base bid for the work was set at 4,500 contos de reis.

The skeptics, who would be more appropriately designated in this case as the elders of Ribeira, were defeated... but not convinced. The first battle was indeed won. Not the war. The Port of Leixões was about to begin construction, but only as a "artificial shelter port." A place where, although some loading and unloading work could be admitted, it was assumed only as a refuge, a safe anchorage for vessels awaiting the best opportunity to enter the Douro bar. Leixões was not yet, in its essence, a true commercial port alternative to that of Douro.

And, when the utility and potential of Leixões were too obvious to ignore, the conservative defenders of Douro attempted one last, radical, and desperate solution: since, indeed, the river mouth was dangerous but the rest of its course along the port quays did not pose great difficulties, and convinced as they were of the safety of Leixões, they proposed (and studies and projects were carried out!) the construction of a canal that, crossing Matosinhos and what is now the waterfront of the city of Porto, would lead vessels from Leixões to the Douro, avoiding its bar. A project that, moreover, had already been considered in 1879 by James Abernethy. Obviously, it was never realized...

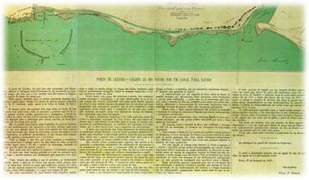

Port of Leixões. With Canal to the Douro River.

George H. Hastings, 1879.

APDL Archive.

The construction process of the Leixões port complex is indeed filled with utopian ideas. Among them, and in addition to the aforementioned canal, it is interesting to highlight the projects and studies aiming at the railway connection of the new port to the city of Porto. In fact, and still following the desires to maintain the prominence of the Douro, the idea prevailed for several decades that such a connection should be made through a branch line that would link Leixões to the Porto Customs House, running along the right bank of the Douro and then, after Foz, along the waterfront. Among the pioneers of this idea, we find the project of William Freebody, dating back to 1854, which proposed laying such a line on piles over the beaches. Today, it would make an interesting tourist route, but its practical application was more than questionable given the usual agitation of the sea and the rough waves that often sweep these beaches!

Pormenor de Plan denoting course of the proposed Line of Tram-way

(planta da proposta de uma linha férrea ligando a cidade do Porto a Leixões, ao longo da orla marítima e da Foz do Douro), incluída no "Relatório de William Freebody". Londres, 1854.

Arquivo da APDL.

Even in the early 20th century, the Porto Merchants' Association advocated for the idea of the Customs House branch line, which is reflected in the project by Engineers Adolpho Loureiro and Santos Viegas in 1907. This project served as a guide for the entire port expansion process throughout the century. However, in this project, the idea that would eventually be effectively implemented already appeared reasonably well developed: the "Circumferential Line," connecting Leixões to Contumil station in Porto, with stops at Leça do Balio and S. Mamede de Infesta. Despite many doubts and hesitations, the official inauguration took place only on September 17, 1938!

Railway connections projects between Porto and the commercial port of Leixões.

Drawing No.1 from the "Project by engineers A. Loureiro and Santos Viegas - variant No.2," 1907.

APDL Archive.

From the beginning of the construction

Or the greatest engineering work in Portugal in the 19th century.

« The ocean is not easily tamed; the spontaneous work of nature is not modified without having to overcome great difficulties.

But science, hydraulic engineering, relying on its powerful resources, was going to start the struggle with the ocean, and was sure to defeat it, not without violent clashes and frequent conflicts with such a valiant opponent".

For its part, the sea gnashed its teeth at hydraulics, sought to regain the ground that science conquered, and, despite being defeated in the struggle, is still not resigned to defeat, still occasionally, as happened last year, throws itself in fury against the port of Leixões to undo it"

Alberto Pimentel, O Porto de Leixões …, 1893

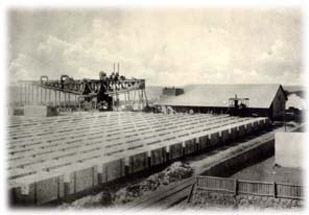

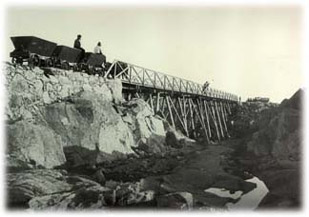

Construction of the Port of Leixões (1884-1892)

Construction yard of the artificial blocks for the North breakwater

Photo: Emílio Biel

Construction of the Port of Leixões (1884-1892)

Construction yard of the artificial blocks for the North breakwater

Photo: Emílio Biel

One of the main challenges in building the breakwaters was exactly how to lift and subsequently deposit the extremely heavy granite blocks in the desired location.

To solve this issue, "Dauderni & Duparchy" commissioned the famous French workshops "Fives" in Lille to build two gigantic and powerful steam-powered cranes that also moved on rails. These cranes, due to their colossal appearance, were immediately dubbed as titans.

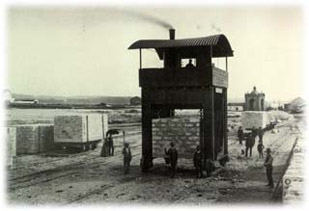

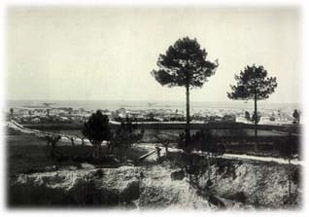

Construction of the Port of Leixões (1884-1892)

North Breakwater seen from the cliffs of Leixões

Photo: Emílio Biel

Construction of the Port of Leixões (1884-1892)

Shipyard of the artificial blocks for the North Breakwater with the Titan being assembled. 1885.

Photo: Emílio Biel

Construction of the Port of Leixões (1884-1892)

Leixões Rocks and ends of the two breakwaters.

Photo: Emílio Biel

Today, these gigantic cranes remain and stand resilient on the breakwaters they built, like two titanic statues erected in memory of the pioneering times of port construction. The crucial importance they held in the context of building this port structure, their grandeur and strength, and the symbolic value they created around themselves throughout the century deserve a closer look.

Mounted in Leixões, the titans, directed during the first years exclusively by a French technician named Lecrit, proved to be indeed fundamental pieces in the port's construction. Gradually, block by block, thanks to their action, the two breakwaters advanced into the sea. Powered by steam (even today it is possible to discern on their tops the "Machine House" with its respective boilers), the titans were effectively used for the construction of the port itself, not as cargo handling cranes as many people think, although they later also performed those functions (at least the one on the south breakwater until the 1960s).

After the construction of the breakwaters, the titans continued to be used for repairs on the walls, resulting from damage caused by the stormy action of the sea. In fact, one of the titans was also the protagonist of a very strong storm that occurred on the night of December 22 to 23, 1892. For the port's memory remains the fall into the sea of the colossus of the north breakwater. Only over three years later, in April 1896, after many studies and efforts, would that titan be recovered from the seabed, with the help of powerful mechanical jacks placed on barges. Quickly restored, the gigantic crane resumed its activity.

Regardless of their importance and significance for Leixões and for the entire region, the titans today have an added importance due to their value as privileged witnesses of the industrial era and of iron architecture/machinery. And they are even more important because apparently they are unique specimens in the world. Because, while it is true that the two titans had other siblings, it is no less true that, in other cases, once the port constructions were completed, these iron giants were dismantled. And when that didn't happen, especially in Europe, the 1st and 2nd World Wars took care of it, considering that maritime ports were early priority bombing targets.

We know of the existence of more titans, such as those in Glasgow (Scotland), or others in Algeria, New Zealand, and in some South American ports. However, they are of smaller dimensions and power, unable to lift the 50 tons that the Leixões titans could raise by steam and iron resistance. Thus, the heritage importance of these cranes already transcends our borders, justifying the fact that in recent years the possibility of their worldwide classification has been suggested several times, similar to the D. Maria Bridge, as an International Mechanical Engineering Historic Landmark.

But let's go back to our history and to the port construction.

Assisting the titans early on, we will find another interesting mechanism: the block lifting apparatus. This mechanism, also steam-powered, transported one by one and via rails the blocks from the shipyards mounted on land to the wagons that later moved them to the titans, in their determined advance over the sea.

Construction of the Port of Leixões (1884-1892)

Crane used to lift and transport on rails the artificial blocks weighing 50 tons, near Senhor do Padrão.

Photo: Emílio Biel

concerning materials de construção, deve-se mention que, apesar do cimento used ser fornecido pela Société des Ciments Françaises, de Boulogne-sur-Mer, a areia foi collected em praias located nas proximidades - também elas connected às obras do porto por carris que led os vagões pulled por locomotivas - e, a pozolana used na composição do cimento era from S. Miguel (Açores).

Construction of the Port of Leixões (1884-1892)

Wooden pontoon for transporting sand to the North breakwater.

Photo: Emílio Biel

The construction of the artificial port of Leixões, which many classify as the greatest engineering feat executed in Portugal in the 19th century, was indeed a national event. It was the materialization and application, in our country, of the undeniable advantages of Progress (read as Technology and Science). Headlining the newspapers of the time, special correspondents reported on the progress of the works. Even the royal family, in full force, traveled in September 1887 to visit the quarries of S. Gens and the works at Leixões. They were essentially repeating what thousands of Porto residents and Northerners in general were doing on weekends: traveling to Matosinhos and Leça da Palmeira to witness the progress of the works.

Construction of the Port of Leixões (1884-1892)

Wooden pier for transporting sand to the North breakwater.

Photo: Emílio Biel

The evolution of the commercial port.

Or the story of a port that ventured inland.

« In the mid-1970s, the partners of Portuguese foreign trade began to change radically, and thus the routes used. As the page of the empire, autarchic dream, and isolation turned, trade shifted towards continental Europe, where TIR traffic development was accelerating (...), limiting the port's function to heavier raw materials and longer voyages. »

François Guichard, The Port in the 20th Century, 1994.

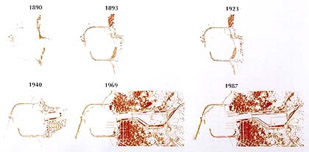

In February 1895, the construction of the harbor was declared completed. However, it was evident the need to transform it into a true commercial port. The number of ships that, as we have seen, still relied on Leixões during its construction, increased overwhelmingly since then. The 409 ships entered the port in 1893 would rise to 665 ten years later. Two decades later, in 1913, their number more than doubled (876 ships). And in 1926, the Douro only handled 22% of the port's traffic.

Nevertheless, the resilient attachment, almost stubborn, of the city of Porto to its old docks on the Douro remains remarkable. Despite the construction of the Leixões harbor in the late 19th century and its subsequent adaptation as a commercial port, and ignoring the shipwrecks that continued to occur at the bar, such as the sinking of the German steamer "Dieister" on February 3, 1929, in which its entire crew of 24 men perished, the Douro still had significant activity in 1931, masterfully captured by Manoel de Oliveira in his first film: "Douro, Faina Fluvial" (1931).

However, it was men, or nature by the hand of men, from the late 1940s onwards, that condemned navigation at the mouth of the Douro. The construction of hydroelectric dams on the river, avoiding the repeated and sometimes gigantic floods, decisively contributed to the decrease in the natural flow and the silting of the Cabedelo. Meanwhile, the tonnage and draft of ships continued to increase...

The Douro, as a commercial port, would disappear during the following two decades. Even characteristic vessels, such as the rabelo boats and the coal barges, were transformed into tourist attractions and decorations.

Products traditionally linked to the river for centuries, such as Port Wine, also began to be exported through Leixões or other means. On March 15, 1963, the ship "Silver Valley" witnessed the last major shipwreck at the bar. In 1971, there was no movement at the Estiva Quay. The one in Gaia would not survive much longer. And by 1976, the river represented only 2% of the port traffic at Douro-Leixões. Today, a residual activity related to the unloading of cement at the Arrábida deposit is the exception that confirms the rule.

Meanwhile, the history of Leixões during this period is characterized by an impressive pace of construction and innovation. As if, over the course of the 20th century, it sought to recover from the delay that had been imposed on it. A real race against time that, while effective in many cases, in many others proved to be already quite late...

But such concern was not always evident. A paradigmatic case was the beginning of the adaptation of the harbor to a commercial port. Indeed, while it is true that when the former was completed in 1895, the evolution to the next stage was already peaceful and desired, it would have to wait for the Republic for such a plan to materialize. In fact, Engineer Henrique Carvalho de Assunção's project aimed at this goal dates back to 1912. And it would be necessary to wait until 1914 for the works to begin. In between was the approval, on April 23, 1913, of a law providing for the transformation of Leixões into a commercial port and the creation of an entity that would manage the construction and operation of this port structure: the Autonomous Board of Maritime Works of the Porto do Douro Leixões. It was this Autonomous Board, at the genesis of the current APDL - Administration of the Ports of Douro and Leixões, that contracted a loan from Caixa Geral de Depósitos with the objective of initiating the works. Loan amount: one thousand contos.

The works consisted of adapting, on the south pier, a dock, about 400 meters long, which allowed its use by ships that could reach depths of up to 23 feet.

Although fundamental and not very complex compared to the construction of the piers shortly before, the truth is that the construction of the dock would drag on for many years. The First World War and the lack of financial resources explain why the work was interrupted from 1916 to 1921. Even so, it would only be completed in 1931. It was already manifestly insufficient, and when the swell intensified, the vessels urgently had to leave the dock...

A quick solution had to be found. And it emerged. But the strategy was different now. The port was no longer conquered from the sea but entered inland, opening up in the estuary of the Leça River itself... Thus, the old and secular shores of Matosinhos and Leça da Palmeira disappeared.

Just two years after the completion of the dock on the south pier, in 1932, the construction of Dock No. 1 began, completed eight years later and solemnly inaugurated on July 4, 1940, with the entry of the warship "Bartolomeu Dias". During this period, the construction of an extensive breakwater at the entrance of the port was also initiated. The company responsible for this intervention was the "Anglo-Dutch Engineering and Harbour Works Co Ltd," while the "Sociedad Metropolitana de Construcción, de Barcelona" undertook the construction of the new dock.

But the reader should not think that the opening of Dock No. 1 was a rare case of rapid conceptualization and construction. The truth is that the idea of using the river valley for the extension of the port complex had already emerged for the first time in 1893 when such a possibility was considered by the commission appointed by the government to study the adaptation of Leixões as a commercial port, led by engineers João Thomaz da Costa and João José Pereira Dinis. Fourteen years later, in 1907, a remarkable project authored by engineers Adolpho Loureiro and Santos Viegas, extensively developed the idea of locating all the docks in the valley. With slight modifications, this project ended up serving as a guiding plan for the entire port expansion process of the 20th century. However, despite being dated 1907, it would be necessary to wait until 1940 for Dock No. 1, with its 550 meters in length and 175 meters in width, with two docking piers totaling one thousand meters, to be inaugurated.

«Port of Leixões. General Plan of the improvement and construction works of the Commercial Port," in Adolpho Loureiro and Santos Viegas,

Port of Leixões. Improvement Project ..., Lisbon, 1908.

The numbers are indicative of what this new dock represented for the port's growth: the 340,000 tons it handled in 1941 quickly rose to 700,000 in 1949 and 900,000 in 1959.

This expansion process drove an ambitious program by Engineer Henrique Schreck who, with rare foresight, anticipated the evolution of maritime traffic and proposed an expansion of port facilities along the Leça valley in 1955. Thus, Dock No. 2 was born, planned to occupy an area of about 500,000 square meters, and whose construction, started in 1956, would extend until the mid-'70s. During this period, however, the port and city's appearance would be significantly altered. Indeed, Henrique Schreck, foreseeing the increasing integration of port traffic with road transport, paid particular attention to the surrounding areas of the port, especially in terms of accessibility. Thus, in addition to the access channels and connections to the dock, and the long berths, warehouses, wide surrounding avenues, viaducts, bridges would multiply... Symbolic of this process is the movable bridge that is now located between Docks No. 1 and No. 2, connecting Matosinhos to Leça da Palmeira. Based on a preliminary design by Engineers Correia de Araújo and Campos Matos, it was built by the company L. Dargent and opened to traffic in 1959.

Expansion of Leixões Commercial Port.

General Plan (scale 1:5000 in the original).

Engineer Henrique Schreck, 1955.

APDL Archive

But the port didn't stop growing. In the late sixties, a terminal for oil tankers was established, and the breakwater, previously submerged, was raised. From 1974 to 1979, a container terminal was built, with a second one of this type (dock No. 3) being completed in the 1990s; between 1974 and 1983, an additional 503 meters of quay were built on the right bank (dock No. 4); in the late eighties, the breakwater was expanded, and in the first half of the nineties, a new marina for sports and recreational boats was constructed. However, the construction of one of the most beloved structures of the Port of Leixões, always desired by the local population, dates back to 1965 to 1968: a fishery port.

Schematic evolution of the port complex of Leixões.

The development of air and road transportation and the profound socio-economic transformations driven by the "Oil Crisis" in the early '70s and the "April 25th" revolution of 1974 posed new and profound challenges to the Porto de Leixões. The end of the hitherto predominant colonial markets. The new realities imposed by the process of European integration. The profound technical and technological development of recent years. All of this required new responses and a marked dynamism that many would have thought impossible for the already century-old port. It is a clear proof that there is no end to history in this case, as in all others. History continues to be made daily. Even when it comes to a structure that has at its base a set of ancient rocks that, for centuries, people have grown accustomed to seeing as a safe harbor.

(1) - Martins 1976, 20-21

(2) - cited in Marçal 1965, 119

(3) - idem, 115

(4) - Cleto 1991

(5) - The Monitor. Matosinhos. 226, February 8, 1891, p.2

(6) - Guichard 1994, 553

(7) - idem

Technical Sheet

In "Porto de Leixões"

Photographs: Domingos Alvão and Emílio Biel

Text: Joel Cleto

Graphic Design: Armando Alves

Edition: Administration of the Ports of Douro and Leixões, 1998